Nazi legacy: The troubled descendantsBy Frances Cronin

BBC News, 23 May 2012

Amon Goeth's daughter Monika only learned the true extent of her father's war crimes when she watched the film Schindler's List

The names of Himmler, Goering, Goeth and Hoess still have the power to evoke the horrors of Nazi Germany, but what is it like to live with the legacy of those surnames, and is it ever possible to move on from the terrible crimes committed by your ancestors?

When he was a child Rainer Hoess was shown a family heirloom.

He remembers his mother lifting the heavy lid of the fireproof chest with a large swastika on the lid, revealing bundles of family photos.

They featured his father as a young child playing with his brothers and sisters, in the garden of their grand family home.

The photos show a pool with a slide and a sand pit - an idyllic family setting - but one that was separated from the gas chambers of Auschwitz by just a few yards.

His grandfather Rudolf Hoess (not to be confused with Nazi deputy leader Rudolf Hess), was the first commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp. His father grew up in a villa adjoining the camp, where he and his siblings played with toys built by prisoners.

It was where his grandmother told the children to wash the strawberries they picked because they smelled of ash from the concentration camp ovens.

Rainer is haunted by the garden gate he spotted in the photos that went straight into the camp - he calls it the "gate to hell".

"It's hard to explain the guilt," says Rainer, "even though there is no reason I should bear any guilt, I still bear it. I carry the guilt with me in my mind.

"I'm ashamed too, of course, for what my family, my grandfather, did to thousands of other families.

"So you ask yourself, they had to die. I'm alive. Why am I alive? To carry this guilt, this burden, to try to come to terms with it.

"That must be the only reason I exist, to do what he should have done."

His father never abandoned the ideology he grew up with and Rainer no longer has contact with him, as he attempts to cope with his family's guilt and shame.

For Katrin Himmler, putting pen to paper was her way of coping with having Heinrich Himmler in her family.

"It's a very heavy burden having someone like that in the family, so close. It's something that just keeps hanging over you."

Himmler, key architect of the Holocaust, was her great-uncle, and her grandfather and his other brother were also in the Nazi party.

She wrote The Himmler Brothers: A German Family History, in a quest to "bring something positive" to the name of Himmler.

"I did my best to distance myself from it and to confront it critically. I no longer need to be ashamed of this family connection."

Rainer Hoess's father (c) plays in a sand pit in the family villa with a gate (r) that leads into Auschwitz

She says the descendants of the Nazi war criminals seem to be caught between two extremes.

"Most decide to cut themselves off entirely from their parents so that they can live their lives, so that the story doesn't destroy them.

"Or they decide on loyalty and unconditional love and sweep all the negative things away."

She says they all face the same question: "Can you really love them if you want to be honest and really know what they did or thought?"

Katrin thought she had a good relationship with her father until she started to research into the family's past. Her father found it very hard to talk about it.

"I could only understand how difficult it was for him when I realised how difficult it was for me to accept that my own grandmother was a Nazi.

"I really loved her, I was fond of her, it was very difficult when I found her letters and learned that she maintained contact with the old Nazis and that she sent a package to a war criminal sentenced to death. It made me feel sick."

Trying to find out exactly what happened in her family's past was hard for Monika Hertwig. She was a baby when her father Amon Goeth was tried and hanged for killing tens of thousands of Jews.

Goeth was the sadistic commander of Plaszow concentration camp, but Monika was brought up by her mother as if the horrors had never happened.

As a child she created a rose-tinted version of her father from family photos.

"I had this image I created [that] the Jews in Plaszow and Amon were one family."

But in her teens she questioned this view of her father and confronted her mother, who eventually admitted her father "may have killed a few Jews".

When she repeatedly asked how many, her mother "became like a madwoman" and whipped her with an electric cable.

It was the film Schindler's List that brought home the full horror of her father's crimes.

Goeth was played by Ralph Fiennes and Monika says watching it "was like being struck".

"I kept thinking this has to stop, at some point they have to stop shooting, because if it doesn't stop I'll go crazy right here in this theatre."

She left the cinema suffering from shock.

For Bettina Goering, the great-niece of Hitler's designated successor Hermann Goering, she felt she needed to take drastic action to deal with her family's legacy.

Both she and her brother chose to be sterilised.

"We both did it... so that there won't be any more Goerings," she explains.

"When my brother had it done, he said to me 'I cut the line'."

Disturbed by her likeness to her great-uncle, she left Germany more than 30 years ago and lives in a remote home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

"It's easier for me to deal with the past of my family from this great distance," she explains.

While Bettina decided to travel far from the site of her relatives' crimes, Rainer Hoess decided he had to visit the heart of his family's shame - Auschwitz.

As a child he was not allowed on school trips to Auschwitz because of his surname, but as an adult in his forties, he felt the need to face "the reality of the horror and the lies I've had all these years in my family".

Seeing his father's childhood home he broke down and kept repeating the word "insanity".

"It's insane what they built here at the expense of others and the gall to say it never happened."

He could not speak when he saw the "gate to hell". In the visitors centre he encountered the raw emotion of descendants of camp victims.

One young Israeli girl broke down as she told him his grandfather had exterminated her family - she could not believe he had chosen to face them.

As Rainer spoke about his guilt and shame, a former Auschwitz prisoner at the back at the room asked if he could shake his hand.

They embraced as Zvika told Rainer how he gives talks to young people, but tells them the relatives are not to blame as they were not there.

For Rainer this was a major moment in dealing with the burden of his family's guilt.

"To receive the approval of someone who survived those horrors and knows for sure that it wasn't you, that you didn't do it.

"For the first time you don't feel fear or shame but happiness, joy, inner joy."

Zvika, holocaust survivor, embraces Rainer Hoess

Bettina Goering chose to be sterilised to ensure the family name did not continue

Schindler's List featured Amon Goeth as a major character

This blog attempts to share new historical information when it appears in other media. Its contents are linked to an understanding of how history is a 'live' subject which undergoes constant historical analysis, explanation and interpretation when new sources and perspectives are shared.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Sunday, May 13, 2012

Remembering May 13: Breaking his silence on a day of tumult

Students marching in the streets in May 1955, with a banner reading 'Victory Parade' in Chinese. They had camped out for a week at Chung Cheng High School and The Chinese High School - both of which had been temporarily closed since May 13 that year - in defiance of the colonial government. -- PHOTOS: ST FILE, LIM CHIN JOO, SEAH KWANG PENG

Mr Lim Chin Joo (seated at table, third from left) as a student leader meeting then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock (with pipe in hand) over the students' camp-in in 1956. -- PHOTOS: ST FILE, LIM CHIN JOO, SEAH KWANG PENG

For years, retired lawyer Lim Chin Joo has been reluctant to go public on an important phase of his life - the time in the 1950s when he was involved in the Chinese middle school students' movement and was arrested for alleged pro-communist activities.

By Leong Weng Kam, Senior Writer

The younger brother of the late leftist trade unionist and politician Lim Chin Siong never accepted invitations to speak at forums or entertained the press for interviews.

Locked up between 1956 and 1966, he studied law while in detention, started practising in 1973 and retired in 1998.

Now 75, and president of the Ee Hoe Hean Club, a gentlemen's club for Chinese businessmen, he has deliberately stayed out of the limelight.

So many were surprised by a notice in the Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao last week, saying he would be speaking today about the three years he spent at The Chinese High School between 1954 and 1956.

The Chinese High School is now part of Hwa Chong Institution. Mr Lim's talk is being jointly organised by the Confucianism Society (Singapore), South Seas Society and the Federation of Chinese Schools' Alumni.

It was Professor Tan Eng Chaw, president of the Confucianism Society and South Seas Society, an academic group, who persuaded him to talk about his turbulent student days to mark the anniversary of Singapore's May 13, 1954 incident.

That day, Chinese middle school students clashed with riot police for the first time. The group was making its way to Government House, now the Istana, to hand a petition to the governor seeking exemption from conscription.

More than 26 people were injured, including a policeman. Some 45 students were arrested after scuffles which led to a mass anti-colonial movement, a political force which helped hasten the process of Singapore obtaining self-government and independence.

'I agreed to speak on the Chinese middle school students' movement which happened more than half a century ago in response to the Government's recent call to build an inclusive society,' Mr Lim told The Sunday Times last week. 'I believe there should be no monopoly of ideas or views by any group or individual.'

In the past, he noted, there were fears that topics such as the leftist student movement were taboo. Most people, especially those involved in past events, had chosen to remain silent.

Mr Lim said he was encouraged to open up now after the recent publication of a number of books on the cause of the Chinese middle school students in the 1950s and 1960s.

They include Xiao Yao You, a collection of interviews in Chinese on the Chinese student activities between 1945 and 1965 put together by The Tangent, a bilingual civil society group, two months ago.

On reading the books, he found there were different versions of what had happened.

'I have developed the urge to offer my version too, being a participant and witness of that part of Singapore history,' he said.

In his talk today, he will speak on why he believes the May 13 incident represented 'a breakthrough in the oppressive atmosphere in Singapore following the declaration of the Emergency in 1948'.

A State of Emergency declared by the colonial government to crack down on the Malayan Communist Party and its sympathisers, which started in Malaya, was extended to Singapore in June 1948. It ended only in 1960.

The Chinese students' petition against conscription, Mr Lim pointed out, questioned openly the legitimacy of colonial rule.

In April 1954, the colonial government had announced that all males between the ages of 18 and 22 were required to register for national service. They included many over-age Chinese middle school students.

But most important of all, he said, the May 13 event brought unity between the students and workers who supported the newly formed political party, the People's Action Party (PAP), led by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, a young lawyer then, and leftist trade unionists such as Mr Lim's elder brother, Chin Siong, and Fong Swee Suan, who were both active in the bus workers' union.

'Without the support of the students, the trade unions and their workers, the PAP could not have swept into power so easily in the 1959 election,' he said.

Mr Lee has a similar view. In his 1998 memoir, The Singapore Story, the former prime minister said his introduction to the world of the Chinese-educated came after the May 13 incident.

It was through the students who sought his help as a lawyer to defend those charged with obstructing police during the incident that Mr Lee got to know Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan.

With their support, the PAP won over the majority Chinese-speaking working-class population and won the crucial 1959 election to form the government.

Mr Lim Chin Joo will also describe the three student camp-ins at The Chinese High School and Chung Cheng High School between June 1954 and October 1956 to protest against a series of actions by the colonial government.

They included the temporary closure of both schools on the eve of the Hock Lee bus riots in May 1955, and the banning of the Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students' Union (SCMSSU) in October 1956, barely a year after it was formed.

Mr Lim was expelled from The Chinese High after police forcibly dispersed the third camp-in on Oct 26, 1956, over the de-registration of SCMSSU. He was among 100 students expelled, ending their 16-day protest on the school grounds.

He joined the leftist General Employees' Union as a paid secretary shortly after, but was arrested by the Lim Yew Hock government for alleged Communist United Front activities in August 1957, a charge he denies to this day.

Reflecting on his eventful youth, Mr Lim said he had kept his views on that period to himself for far too long.

'Those who have witnessed the course of history have a duty to leave behind their memories,' he added.

wengkam@sph.com.sg

Mr Lim Chin Joo's talk, in Mandarin, on his three years at the former The Chinese High School will be held at Hwa Chong Institution's High School Auditorium (Clock Tower Block) today at 2.30pm and 4.30pm. Admission is free

Students marching in the streets in May 1955, with a banner reading 'Victory Parade' in Chinese. They had camped out for a week at Chung Cheng High School and The Chinese High School - both of which had been temporarily closed since May 13 that year - in defiance of the colonial government. -- PHOTOS: ST FILE, LIM CHIN JOO, SEAH KWANG PENG

Mr Lim Chin Joo (seated at table, third from left) as a student leader meeting then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock (with pipe in hand) over the students' camp-in in 1956. -- PHOTOS: ST FILE, LIM CHIN JOO, SEAH KWANG PENG

For years, retired lawyer Lim Chin Joo has been reluctant to go public on an important phase of his life - the time in the 1950s when he was involved in the Chinese middle school students' movement and was arrested for alleged pro-communist activities.

By Leong Weng Kam, Senior Writer

The younger brother of the late leftist trade unionist and politician Lim Chin Siong never accepted invitations to speak at forums or entertained the press for interviews.

Locked up between 1956 and 1966, he studied law while in detention, started practising in 1973 and retired in 1998.

Now 75, and president of the Ee Hoe Hean Club, a gentlemen's club for Chinese businessmen, he has deliberately stayed out of the limelight.

So many were surprised by a notice in the Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao last week, saying he would be speaking today about the three years he spent at The Chinese High School between 1954 and 1956.

The Chinese High School is now part of Hwa Chong Institution. Mr Lim's talk is being jointly organised by the Confucianism Society (Singapore), South Seas Society and the Federation of Chinese Schools' Alumni.

It was Professor Tan Eng Chaw, president of the Confucianism Society and South Seas Society, an academic group, who persuaded him to talk about his turbulent student days to mark the anniversary of Singapore's May 13, 1954 incident.

That day, Chinese middle school students clashed with riot police for the first time. The group was making its way to Government House, now the Istana, to hand a petition to the governor seeking exemption from conscription.

More than 26 people were injured, including a policeman. Some 45 students were arrested after scuffles which led to a mass anti-colonial movement, a political force which helped hasten the process of Singapore obtaining self-government and independence.

'I agreed to speak on the Chinese middle school students' movement which happened more than half a century ago in response to the Government's recent call to build an inclusive society,' Mr Lim told The Sunday Times last week. 'I believe there should be no monopoly of ideas or views by any group or individual.'

In the past, he noted, there were fears that topics such as the leftist student movement were taboo. Most people, especially those involved in past events, had chosen to remain silent.

Mr Lim said he was encouraged to open up now after the recent publication of a number of books on the cause of the Chinese middle school students in the 1950s and 1960s.

They include Xiao Yao You, a collection of interviews in Chinese on the Chinese student activities between 1945 and 1965 put together by The Tangent, a bilingual civil society group, two months ago.

On reading the books, he found there were different versions of what had happened.

'I have developed the urge to offer my version too, being a participant and witness of that part of Singapore history,' he said.

In his talk today, he will speak on why he believes the May 13 incident represented 'a breakthrough in the oppressive atmosphere in Singapore following the declaration of the Emergency in 1948'.

A State of Emergency declared by the colonial government to crack down on the Malayan Communist Party and its sympathisers, which started in Malaya, was extended to Singapore in June 1948. It ended only in 1960.

The Chinese students' petition against conscription, Mr Lim pointed out, questioned openly the legitimacy of colonial rule.

In April 1954, the colonial government had announced that all males between the ages of 18 and 22 were required to register for national service. They included many over-age Chinese middle school students.

But most important of all, he said, the May 13 event brought unity between the students and workers who supported the newly formed political party, the People's Action Party (PAP), led by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, a young lawyer then, and leftist trade unionists such as Mr Lim's elder brother, Chin Siong, and Fong Swee Suan, who were both active in the bus workers' union.

'Without the support of the students, the trade unions and their workers, the PAP could not have swept into power so easily in the 1959 election,' he said.

Mr Lee has a similar view. In his 1998 memoir, The Singapore Story, the former prime minister said his introduction to the world of the Chinese-educated came after the May 13 incident.

It was through the students who sought his help as a lawyer to defend those charged with obstructing police during the incident that Mr Lee got to know Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan.

With their support, the PAP won over the majority Chinese-speaking working-class population and won the crucial 1959 election to form the government.

Mr Lim Chin Joo will also describe the three student camp-ins at The Chinese High School and Chung Cheng High School between June 1954 and October 1956 to protest against a series of actions by the colonial government.

They included the temporary closure of both schools on the eve of the Hock Lee bus riots in May 1955, and the banning of the Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students' Union (SCMSSU) in October 1956, barely a year after it was formed.

Mr Lim was expelled from The Chinese High after police forcibly dispersed the third camp-in on Oct 26, 1956, over the de-registration of SCMSSU. He was among 100 students expelled, ending their 16-day protest on the school grounds.

He joined the leftist General Employees' Union as a paid secretary shortly after, but was arrested by the Lim Yew Hock government for alleged Communist United Front activities in August 1957, a charge he denies to this day.

Reflecting on his eventful youth, Mr Lim said he had kept his views on that period to himself for far too long.

'Those who have witnessed the course of history have a duty to leave behind their memories,' he added.

wengkam@sph.com.sg

Mr Lim Chin Joo's talk, in Mandarin, on his three years at the former The Chinese High School will be held at Hwa Chong Institution's High School Auditorium (Clock Tower Block) today at 2.30pm and 4.30pm. Admission is free

Friday, May 11, 2012

Kahlil Gibran

Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet: Why is it so loved?By Shoku Amirani & Stephanie Hegarty BBC World Service

Kahlil Gibran is said to be one of the world's bestselling poets, and his life has inspired a play touring the UK and the Middle East. But many critics have been lukewarm about his merits. Why, then, has his seminal work, The Prophet, struck such a chord with generations of readers? Since it was published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. The perennial classic has been translated into more than 50 languages and is a staple on international bestseller lists. It is thought to have sold tens of millions of copies.

Although practically ignored by the literary establishment in the West, lines from the book have inspired song lyrics, political speeches and have been read out at weddings and funerals all around the world. "It serves various occasions or big moments in one's life so it tends to be a book that is often gifted to a lover, or for a birth, or death. That is why it has spread so widely, and by word of mouth," says Dr Mohamed Salah Omri, lecturer in Modern Arabic literature at Oxford University. The Beatles, John F Kennedy and Indira Gandhi are among those who have been influenced by its words.

"This book has a way of speaking to people at different stages in their lives. It has this magical quality, the more you read it the more you come to understand the words," says Reverend Laurie Sue, an interfaith minister in New York who has conducted hundreds of weddings with readings from The Prophet. "But it is not filled with any kind of dogma, it is available to anyone whether they are Jewish or Christian or Muslim."

The book is made up of 26 prose poems, delivered as sermons by a wise man called Al Mustapha. He is about to set sail for his homeland after 12 years in exile on a fictional island when the people of the island ask him to share his wisdom on the big questions of life: love, family, work and death. Its popularity peaked in the 1930s and again in the 1960s when it became the bible of the counter culture.

"Many people turned away from the establishment of the Church to Gibran," says Professor Juan Cole, historian of the Middle East at Michigan University who has translated several of Gibran's works from Arabic. "He offered a dogma-free universal spiritualism as opposed to orthodox religion, and his vision of the spiritual was not moralistic. In fact, he urged people to be non-judgmental."

Despite the immense popularity of his writing, or perhaps because of it, The Prophet was panned by many critics in the West who thought it simplistic, naive and lacking in substance.

"In the West, he was not added to the canon of English literature," says Cole. "Even though his major works were in English after 1918, and though he is one of bestselling poets in American history, he was disdained by English professors."

"He was looked down upon as, frankly, a 'bubblehead' by Western academics, because he appealed to the masses. I think he has been misunderstood in the West. He is certainly not a bubblehead, in fact his writings in Arabic are in a very sophisticated style.

"There is no doubt he deserves a place in the Western canon. It is strange to teach English literature and ignore a literary phenomenon."

Gibran was a painter as well as a writer by training and was schooled in the symbolist tradition in Paris in 1908. He mixed with the intellectual elite of his time, including figures such as WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin, all of whom he met and painted. Symbolists such as Rodin and the English poet and artist William Blake, who was a big influence on Gibran, favoured romance over realism and it was a movement that was already passe in the 1920s as modernists such as TS Eliot and Ezra Pound were gaining popularity. He painted more than 700 pictures, watercolours and drawings but because most of his paintings were shipped back to Lebanon after his death, they have been overlooked in the West. Professor Suheil Bushrui, who holds the Kahlil Gibran chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland, compares Gibran to the English Romantics such as Shelly and Blake, and he says that like Gibran, Blake was dismissed in his own time. "He was called 'mad Blake'. He is now a major figure in English literature. So the fact that a writer is not taken seriously by the critics is no indication of the value of the work". In Lebanon, where he was born, he is still celebrated as a literary hero.

His style, which broke away from the classical school, pioneered a new Romantic movement in Arabic literature of poetic prose.

"We are talking about a renaissance in modern Arabic literature and this renaissance had at its foundation Gibran's writings," says Professor Suheil Bushrui, who holds the Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland.

In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a rebel, both in a literary and political sense. He emigrated to the US at 12 but returned to study in Lebanon three years later where he witnessed injustices suffered by peasants at the hands of their Ottoman rulers. "He was a Christian but he saw things being done in the name of Christianity which he could not accept," says Bushrui.

In his writing, he raged against the oppression of women and the tyranny of the Church and called for freedom from Ottoman rule. "What he was doing was revolutionary and there were protests against it in the Arab world," says Juan Cole. "So he is viewed in Arabic literature as an innovator, not dissimilar to someone like WB Yeats in the West."

Political leaders considered his thoughts poisonous to young people and one of his books, Spirit Rebellious, was burnt in the market place in Beirut soon after it was published. By the 1930s, Gibran had become a prominent and charismatic figure within the Lebanese community and New York literary circles.

But the success of his writing in English owes much to a woman called Mary Haskell, a progressive Boston school headmistress who became his patron and confidante as well as his editor. Haskell supported him financially throughout his career until the publication of The Prophet in 1923. Their relationship developed into a love affair and although Gibran proposed to her twice, they never married. Haskell's conservative family at that time would never have accepted her marrying an immigrant, says Jean Gibran, who married Kahlil Gibran's godson and his namesake and dedicated five years to writing a biography of the writer.

In their book, Jean Gibran and her late husband didn't shy away from the less favourable aspects of the Gibran's character. He was, they admit, known to cultivate his own celebrity.

He even went so far as to create a mythology around himself and made pretensions to a noble lineage. But Jean Gibran says that he never claimed to be a saint or prophet. "As a poor but proud immigrant amongst Boston's elite, he didn't want people to look down on him. He was a fragile human being and aware of his own weaknesses." But arguably for Gibran's English readers, none of this mattered much. "I don't know how many people who picked up The Prophet, read it or gifted it, would actually know about Gibran the man or even want to know," says Dr Mohamed Salah Omri. "Part of the appeal is perhaps that this book could have been written by anybody and that is what we do with scripture. It just is."

Man Behind the Prophet Programme: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00r49dp A poet's life

Born to Maronite Catholic family in Lebanon, 1883

Moves to US aged 12 with mother and siblings after father imprisoned for embezzlement

Settles in South Boston's Lebanese community

Clerical error at school registers his name as Kahlil, not Khalil

He was a talented pupil and came to the attention of local artist and photographer Fred Holland Day Returns to Lebanon at 15 to study Arabic

Soon after, he lost his mother, sister and brother to TB and cancer within months of each other

Back in the US in 1904, he meets Mary Haskell

In 1908, goes to Paris for two years to study art in the symbolist school First book of poetry published in 1918, then The Prophet five years later

Dies in 1931 from cirrhosis of the liver and TB

Inspires a play Rest Upon the Wind, which tours UK and Middle East in 2012

Kahlil Gibran is said to be one of the world's bestselling poets, and his life has inspired a play touring the UK and the Middle East. But many critics have been lukewarm about his merits. Why, then, has his seminal work, The Prophet, struck such a chord with generations of readers? Since it was published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. The perennial classic has been translated into more than 50 languages and is a staple on international bestseller lists. It is thought to have sold tens of millions of copies.

Although practically ignored by the literary establishment in the West, lines from the book have inspired song lyrics, political speeches and have been read out at weddings and funerals all around the world. "It serves various occasions or big moments in one's life so it tends to be a book that is often gifted to a lover, or for a birth, or death. That is why it has spread so widely, and by word of mouth," says Dr Mohamed Salah Omri, lecturer in Modern Arabic literature at Oxford University. The Beatles, John F Kennedy and Indira Gandhi are among those who have been influenced by its words.

"This book has a way of speaking to people at different stages in their lives. It has this magical quality, the more you read it the more you come to understand the words," says Reverend Laurie Sue, an interfaith minister in New York who has conducted hundreds of weddings with readings from The Prophet. "But it is not filled with any kind of dogma, it is available to anyone whether they are Jewish or Christian or Muslim."

The book is made up of 26 prose poems, delivered as sermons by a wise man called Al Mustapha. He is about to set sail for his homeland after 12 years in exile on a fictional island when the people of the island ask him to share his wisdom on the big questions of life: love, family, work and death. Its popularity peaked in the 1930s and again in the 1960s when it became the bible of the counter culture.

"Many people turned away from the establishment of the Church to Gibran," says Professor Juan Cole, historian of the Middle East at Michigan University who has translated several of Gibran's works from Arabic. "He offered a dogma-free universal spiritualism as opposed to orthodox religion, and his vision of the spiritual was not moralistic. In fact, he urged people to be non-judgmental."

Despite the immense popularity of his writing, or perhaps because of it, The Prophet was panned by many critics in the West who thought it simplistic, naive and lacking in substance.

"In the West, he was not added to the canon of English literature," says Cole. "Even though his major works were in English after 1918, and though he is one of bestselling poets in American history, he was disdained by English professors."

"He was looked down upon as, frankly, a 'bubblehead' by Western academics, because he appealed to the masses. I think he has been misunderstood in the West. He is certainly not a bubblehead, in fact his writings in Arabic are in a very sophisticated style.

"There is no doubt he deserves a place in the Western canon. It is strange to teach English literature and ignore a literary phenomenon."

Gibran was a painter as well as a writer by training and was schooled in the symbolist tradition in Paris in 1908. He mixed with the intellectual elite of his time, including figures such as WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin, all of whom he met and painted. Symbolists such as Rodin and the English poet and artist William Blake, who was a big influence on Gibran, favoured romance over realism and it was a movement that was already passe in the 1920s as modernists such as TS Eliot and Ezra Pound were gaining popularity. He painted more than 700 pictures, watercolours and drawings but because most of his paintings were shipped back to Lebanon after his death, they have been overlooked in the West. Professor Suheil Bushrui, who holds the Kahlil Gibran chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland, compares Gibran to the English Romantics such as Shelly and Blake, and he says that like Gibran, Blake was dismissed in his own time. "He was called 'mad Blake'. He is now a major figure in English literature. So the fact that a writer is not taken seriously by the critics is no indication of the value of the work". In Lebanon, where he was born, he is still celebrated as a literary hero.

His style, which broke away from the classical school, pioneered a new Romantic movement in Arabic literature of poetic prose.

"We are talking about a renaissance in modern Arabic literature and this renaissance had at its foundation Gibran's writings," says Professor Suheil Bushrui, who holds the Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland.

In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a rebel, both in a literary and political sense. He emigrated to the US at 12 but returned to study in Lebanon three years later where he witnessed injustices suffered by peasants at the hands of their Ottoman rulers. "He was a Christian but he saw things being done in the name of Christianity which he could not accept," says Bushrui.

In his writing, he raged against the oppression of women and the tyranny of the Church and called for freedom from Ottoman rule. "What he was doing was revolutionary and there were protests against it in the Arab world," says Juan Cole. "So he is viewed in Arabic literature as an innovator, not dissimilar to someone like WB Yeats in the West."

Political leaders considered his thoughts poisonous to young people and one of his books, Spirit Rebellious, was burnt in the market place in Beirut soon after it was published. By the 1930s, Gibran had become a prominent and charismatic figure within the Lebanese community and New York literary circles.

But the success of his writing in English owes much to a woman called Mary Haskell, a progressive Boston school headmistress who became his patron and confidante as well as his editor. Haskell supported him financially throughout his career until the publication of The Prophet in 1923. Their relationship developed into a love affair and although Gibran proposed to her twice, they never married. Haskell's conservative family at that time would never have accepted her marrying an immigrant, says Jean Gibran, who married Kahlil Gibran's godson and his namesake and dedicated five years to writing a biography of the writer.

In their book, Jean Gibran and her late husband didn't shy away from the less favourable aspects of the Gibran's character. He was, they admit, known to cultivate his own celebrity.

He even went so far as to create a mythology around himself and made pretensions to a noble lineage. But Jean Gibran says that he never claimed to be a saint or prophet. "As a poor but proud immigrant amongst Boston's elite, he didn't want people to look down on him. He was a fragile human being and aware of his own weaknesses." But arguably for Gibran's English readers, none of this mattered much. "I don't know how many people who picked up The Prophet, read it or gifted it, would actually know about Gibran the man or even want to know," says Dr Mohamed Salah Omri. "Part of the appeal is perhaps that this book could have been written by anybody and that is what we do with scripture. It just is."

Man Behind the Prophet Programme: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00r49dp A poet's life

Born to Maronite Catholic family in Lebanon, 1883

Moves to US aged 12 with mother and siblings after father imprisoned for embezzlement

Settles in South Boston's Lebanese community

Clerical error at school registers his name as Kahlil, not Khalil

He was a talented pupil and came to the attention of local artist and photographer Fred Holland Day Returns to Lebanon at 15 to study Arabic

Soon after, he lost his mother, sister and brother to TB and cancer within months of each other

Back in the US in 1904, he meets Mary Haskell

In 1908, goes to Paris for two years to study art in the symbolist school First book of poetry published in 1918, then The Prophet five years later

Dies in 1931 from cirrhosis of the liver and TB

Inspires a play Rest Upon the Wind, which tours UK and Middle East in 2012

WWII Kittyhawk Discovered Intact

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-18038650 A World War II RAF fighter, which crash-landed in a remote part of the Egyptian desert in 1942, has been discovered almost intact.

There was no trace of the pilot, Flt Sgt Dennis Copping, but the British embassy says it is planning to mount a search for his remains. The RAF Museum in Hendon, north London, says it is hoping to recover the plane as soon as possible. There are fears souvenir hunters will start stripping it. The 24-year-old pilot, the son of a dentist from Southend in Essex, went missing over the Western Desert in June 1942, flying an American-made P40 Kittyhawk single-engine fighter.

Two-and-a-half months ago an aircraft believed to be his was discovered near a remote place called Wadi al-Jadid by a Polish oil worker, Jakub Perka. His photographs show the plane is in remarkably good condition, though the engine and propeller have separated from the fuselage. The original paintwork and RAF insignia are said to be clearly visible, almost perfectly preserved in the dry desert air. But of the pilot there is no sign. He appears to have executed a near-perfect emergency landing, perhaps after becoming lost and running out of fuel, and to have survived the crash He rigged a parachute as an awning and removed the aircraft's radio and batteries but then apparently walked off into the desert in search of help.

Bleak prospects

Almost 100 miles from the nearest settlement, he stood virtually no chance. David Keen, an aviation historian at the RAF Museum, says the pilot broke the first rule of survival in the desert, which is to stay with your plane or vehicle. But the very same conditions which made the pilot's prospects so bleak have helped preserve the plane. Mr Keen says of the many thousands of aircraft which were shot down or crashed during the Second World War, very few survive in anything like this condition. He said: "Nearly all the crashes in the Second World War, and there were tens of thousands of them, resulted on impact with the aircraft breaking up, so the only bits that are recovered are fragments, often scattered over a wide area. "What makes this particular aircraft so special is that it looks complete, and it survived on the surface of the desert all these years. It's like a timewarp." The RAF Museum has a P40 Kittyhawk on display, but it has been put together from parts of many different aircraft. Recovering Flt Sgt Copping's plane will not be easy. Souvenir hunters

It is in a part of the desert which is not only remote but also dangerous, because it is close to a smuggling route between Libya and Egypt.

The defence attache at the British Embassy in Cairo, Paul Collins, says he is hoping to travel to the area in the near future, but is waiting for permission from the Egyptian army. He told the BBC: "I have to go down there. This is a serviceman who was killed, albeit 70 years ago. We have a responsibility to go and find out whether it's his plane, though not necessarily to work out what happened. "He went missing in action. We can only assume he got out and walked somewhere, so we have to do a search of the area for any remains, although it could be a wide area. "But we have to go soon as all the souvenir hunters will be down there," said Mr Collins. He said the British authorities are trying to find out whether Flt Sgt Copping has any surviving close relatives, because if his remains are found a decision will need to be made about what to do with them.

There was no trace of the pilot, Flt Sgt Dennis Copping, but the British embassy says it is planning to mount a search for his remains. The RAF Museum in Hendon, north London, says it is hoping to recover the plane as soon as possible. There are fears souvenir hunters will start stripping it. The 24-year-old pilot, the son of a dentist from Southend in Essex, went missing over the Western Desert in June 1942, flying an American-made P40 Kittyhawk single-engine fighter.

Two-and-a-half months ago an aircraft believed to be his was discovered near a remote place called Wadi al-Jadid by a Polish oil worker, Jakub Perka. His photographs show the plane is in remarkably good condition, though the engine and propeller have separated from the fuselage. The original paintwork and RAF insignia are said to be clearly visible, almost perfectly preserved in the dry desert air. But of the pilot there is no sign. He appears to have executed a near-perfect emergency landing, perhaps after becoming lost and running out of fuel, and to have survived the crash He rigged a parachute as an awning and removed the aircraft's radio and batteries but then apparently walked off into the desert in search of help.

Bleak prospects

Almost 100 miles from the nearest settlement, he stood virtually no chance. David Keen, an aviation historian at the RAF Museum, says the pilot broke the first rule of survival in the desert, which is to stay with your plane or vehicle. But the very same conditions which made the pilot's prospects so bleak have helped preserve the plane. Mr Keen says of the many thousands of aircraft which were shot down or crashed during the Second World War, very few survive in anything like this condition. He said: "Nearly all the crashes in the Second World War, and there were tens of thousands of them, resulted on impact with the aircraft breaking up, so the only bits that are recovered are fragments, often scattered over a wide area. "What makes this particular aircraft so special is that it looks complete, and it survived on the surface of the desert all these years. It's like a timewarp." The RAF Museum has a P40 Kittyhawk on display, but it has been put together from parts of many different aircraft. Recovering Flt Sgt Copping's plane will not be easy. Souvenir hunters

It is in a part of the desert which is not only remote but also dangerous, because it is close to a smuggling route between Libya and Egypt.

The defence attache at the British Embassy in Cairo, Paul Collins, says he is hoping to travel to the area in the near future, but is waiting for permission from the Egyptian army. He told the BBC: "I have to go down there. This is a serviceman who was killed, albeit 70 years ago. We have a responsibility to go and find out whether it's his plane, though not necessarily to work out what happened. "He went missing in action. We can only assume he got out and walked somewhere, so we have to do a search of the area for any remains, although it could be a wide area. "But we have to go soon as all the souvenir hunters will be down there," said Mr Collins. He said the British authorities are trying to find out whether Flt Sgt Copping has any surviving close relatives, because if his remains are found a decision will need to be made about what to do with them.

Horst Faas - War photographer

(A guerrilla leader in Dhaka, Bangladesh, beat a victim during a public execution of four men suspected of collaborating with Pakistani militiamen, who were accused of murder, rape and looting during months of civil war. 1971.)

Horst Faas, a prizewinning combat photographer who carved out new standards for covering war with a camera and became one of the world’s distinguished photojournalists in nearly a half-century with The Associated Press, died on Thursday. He was 79.

His daughter, Clare Faas, confirmed his death. A native of Germany who joined The Associated Press there in 1956, Mr. Faas photographed wars, revolutions, the Olympic Games and events in between. But he was best known for covering Vietnam, where he was severely wounded in 1967 and won four major photo awards including the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes.

As chief of The A.P.’s photo operations in Saigon for a decade beginning in 1962, Mr. Faas covered the fighting while recruiting and training new talent from among foreign and Vietnamese freelancers. The result was “Horst’s army” of young photographers, who fanned out with supplied cameras and film supplied by Mr. Faas and stern orders to “come back with good pictures Mr. Faas and his editors chose the best and put together a steady flow of telling photos: South Vietnam’s soldiers fighting and its civilians struggling to survive amid the maelstrom.

Among his top protégés was Huynh Thanh My, an actor turned photographer who in 1965 became one of four A.P. staff photographers and one of two South Vietnamese among more than 70 journalists killed in the 15-year war. Mr. My’s younger brother, Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut, followed his brother at The A.P. and under Mr. Faas’s tutelage won one of the news agency’s six Vietnam War Pulitzer Prizes, for his iconic 1972 picture of a badly burned Vietnamese girl fleeing an aerial napalm attack.

Mr. Faas was a brilliant planner, able to score journalistic scoops by anticipating “not just what happens next, but what happens after that,” as one colleague put it. His reputation as a demanding taskmaster and perfectionist belied a humanistic streak he was loath to admit, while helping less fortunate former colleagues and other causes. He was widely read on Asian history and culture, and assembled an impressive collection of Chinese Ming porcelain, bronzes and other treasures.

In later years, Mr. Faas turned his training skills into a series of international photojournalism symposiums. Mr. Faas also helped to organize reunions of the wartime Saigon news corps, and was attending a combination of those events when he became ill in Hanoi on May 4, 2005.

He was hospitalized first in Bangkok, then in Germany, where doctors traced his permanent paralysis from the waist down to a spinal hemorrhage caused by blood-thinning heart medication. Although he required a wheelchair, he continued to travel to photo exhibits and other professional events, mainly in Europe, and collaborated in the publishing of two books in French — about his own career and that of Henri Huet, a former A.P. colleague in Vietnam.

Mr. Faas also made two trips to the United States, in 2006 and in 2008. His health deteriorated in late 2008. Hospitalized in February for treatment of skin problems, he also underwent gastric surgery. Mr. Faas’s Vietnam coverage earned him the Overseas Press Club’s Robert Capa Award and his first Pulitzer in 1965. Receiving the honors in New York, he said his mission was to “record the suffering, the emotions and the sacrifices of both Americans and Vietnamese” in Vietnam.

Burly but agile, Mr. Faas spent much time in the field, and on Dec. 6, 1967, he was wounded in the legs by a rocket-propelled grenade at Bu Dop, in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. He might have bled to death had not a young U.S. Army medic managed to stem the flow.

Meeting Mr. Faas two decades later, the medic recalled the encounter, saying, “You were so gray, I thought you were a goner.” On crutches and confined to the bureau, Mr. Faas was unable to cover the February 1968 Tet Offensive, but directed A.P. photo operations like a general deploying troops against the enemy.

The A.P. photographer Eddie Adams came back with the war’s most famous picture, of Vietnam’s national police chief executing a captured Vietcong suspect on a Saigon street. “Generally, we had to go pretty far into the field, but this was a situation in which the war came to us,” Mr. Faas recalled. “It was right next door.”

He often teamed with the Pulitzer Prize-winning A.P. reporter Peter Arnett to produce powerful and exclusive reports like the 1969 story of Co. A, an Army unit that balked at orders to move against the enemy. Mr. Faas witnessed the “combat refusal” episode during an effort to reach the site of a helicopter crash that had killed seven U.S. soldiers and the A.P. staff photographer Oliver E. Noonan.

Born in Berlin on April 28, 1933, Mr. Faas grew up during World War II, and like all young German men, was required to join the Hitler Youth organization. Years later, he wrote that Allied air raids and “the fascinating spectacle of antiaircraft action in the sky” were part of daily life, as was being required “to stand at attention in school and listen to an announcement that the father or older brother of a classmate had died for führer and Fatherland.”

As the war ended in 1945, the family fled north to avoid the Russian advance on Berlin, and two years later, escaped to Munich in West Germany. In 1960, at age 27 and having been an A.P. photographer for four years, Mr. Faas began his front-line reporting career in Congo, then Algeria.

In 1962, he was reassigned to the growing war in Vietnam where he landed on the same day as Mr. Arnett. Mr. Faas for a time shared a Saigon villa with the late New York Times correspondent David Halberstam, who said of Mr. Faas, “I don’t think anyone stayed longer, took more risks or showed greater devotion to his work and his colleagues. I think of him as nothing less than a genius.”

Mr. Faas left Saigon in 1970 to become the A.P.’s roving photographer for Asia, based in Singapore, ranging widely on assignments. He teamed with Mr. Arnett, a New Zealander, on a cross-country reporting tour of the United States as seen by foreigners, and covered the 1972 Munich Olympics where he photographed a ski-masked Palestinian terrorist on the balcony of the building where Israeli athletes were being held hostage, hours before they were murdered at the airport.

The same year, he won a second Pulitzer Prize, along with Michel Laurent of the French Gamma photo agency, for gripping pictures of torture and executions in Bangladesh.

Mr. Laurent, who had once worked for The A.P. under Mr. Faas in Saigon, later became the last journalist killed in the Vietnam War, two days before the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. In 1976, Mr. Faas relocated to London as The A.P.’s senior photo editor for Europe, until he retired from the news agency in 2004. He was an editor of “Requiem,” a 1997 book about photographers killed on both sides of the Vietnam War, and was an author of “Lost Over Laos,” a 2003 book about four photographers shot down in Laos in 1971 and the search for the crash site 27 years later. http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/a-parting-glance-horst-faas/

Horst Faas, a prizewinning combat photographer who carved out new standards for covering war with a camera and became one of the world’s distinguished photojournalists in nearly a half-century with The Associated Press, died on Thursday. He was 79.

His daughter, Clare Faas, confirmed his death. A native of Germany who joined The Associated Press there in 1956, Mr. Faas photographed wars, revolutions, the Olympic Games and events in between. But he was best known for covering Vietnam, where he was severely wounded in 1967 and won four major photo awards including the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes.

As chief of The A.P.’s photo operations in Saigon for a decade beginning in 1962, Mr. Faas covered the fighting while recruiting and training new talent from among foreign and Vietnamese freelancers. The result was “Horst’s army” of young photographers, who fanned out with supplied cameras and film supplied by Mr. Faas and stern orders to “come back with good pictures Mr. Faas and his editors chose the best and put together a steady flow of telling photos: South Vietnam’s soldiers fighting and its civilians struggling to survive amid the maelstrom.

Among his top protégés was Huynh Thanh My, an actor turned photographer who in 1965 became one of four A.P. staff photographers and one of two South Vietnamese among more than 70 journalists killed in the 15-year war. Mr. My’s younger brother, Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut, followed his brother at The A.P. and under Mr. Faas’s tutelage won one of the news agency’s six Vietnam War Pulitzer Prizes, for his iconic 1972 picture of a badly burned Vietnamese girl fleeing an aerial napalm attack.

Mr. Faas was a brilliant planner, able to score journalistic scoops by anticipating “not just what happens next, but what happens after that,” as one colleague put it. His reputation as a demanding taskmaster and perfectionist belied a humanistic streak he was loath to admit, while helping less fortunate former colleagues and other causes. He was widely read on Asian history and culture, and assembled an impressive collection of Chinese Ming porcelain, bronzes and other treasures.

In later years, Mr. Faas turned his training skills into a series of international photojournalism symposiums. Mr. Faas also helped to organize reunions of the wartime Saigon news corps, and was attending a combination of those events when he became ill in Hanoi on May 4, 2005.

He was hospitalized first in Bangkok, then in Germany, where doctors traced his permanent paralysis from the waist down to a spinal hemorrhage caused by blood-thinning heart medication. Although he required a wheelchair, he continued to travel to photo exhibits and other professional events, mainly in Europe, and collaborated in the publishing of two books in French — about his own career and that of Henri Huet, a former A.P. colleague in Vietnam.

Mr. Faas also made two trips to the United States, in 2006 and in 2008. His health deteriorated in late 2008. Hospitalized in February for treatment of skin problems, he also underwent gastric surgery. Mr. Faas’s Vietnam coverage earned him the Overseas Press Club’s Robert Capa Award and his first Pulitzer in 1965. Receiving the honors in New York, he said his mission was to “record the suffering, the emotions and the sacrifices of both Americans and Vietnamese” in Vietnam.

Burly but agile, Mr. Faas spent much time in the field, and on Dec. 6, 1967, he was wounded in the legs by a rocket-propelled grenade at Bu Dop, in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. He might have bled to death had not a young U.S. Army medic managed to stem the flow.

Meeting Mr. Faas two decades later, the medic recalled the encounter, saying, “You were so gray, I thought you were a goner.” On crutches and confined to the bureau, Mr. Faas was unable to cover the February 1968 Tet Offensive, but directed A.P. photo operations like a general deploying troops against the enemy.

The A.P. photographer Eddie Adams came back with the war’s most famous picture, of Vietnam’s national police chief executing a captured Vietcong suspect on a Saigon street. “Generally, we had to go pretty far into the field, but this was a situation in which the war came to us,” Mr. Faas recalled. “It was right next door.”

He often teamed with the Pulitzer Prize-winning A.P. reporter Peter Arnett to produce powerful and exclusive reports like the 1969 story of Co. A, an Army unit that balked at orders to move against the enemy. Mr. Faas witnessed the “combat refusal” episode during an effort to reach the site of a helicopter crash that had killed seven U.S. soldiers and the A.P. staff photographer Oliver E. Noonan.

Born in Berlin on April 28, 1933, Mr. Faas grew up during World War II, and like all young German men, was required to join the Hitler Youth organization. Years later, he wrote that Allied air raids and “the fascinating spectacle of antiaircraft action in the sky” were part of daily life, as was being required “to stand at attention in school and listen to an announcement that the father or older brother of a classmate had died for führer and Fatherland.”

As the war ended in 1945, the family fled north to avoid the Russian advance on Berlin, and two years later, escaped to Munich in West Germany. In 1960, at age 27 and having been an A.P. photographer for four years, Mr. Faas began his front-line reporting career in Congo, then Algeria.

In 1962, he was reassigned to the growing war in Vietnam where he landed on the same day as Mr. Arnett. Mr. Faas for a time shared a Saigon villa with the late New York Times correspondent David Halberstam, who said of Mr. Faas, “I don’t think anyone stayed longer, took more risks or showed greater devotion to his work and his colleagues. I think of him as nothing less than a genius.”

Mr. Faas left Saigon in 1970 to become the A.P.’s roving photographer for Asia, based in Singapore, ranging widely on assignments. He teamed with Mr. Arnett, a New Zealander, on a cross-country reporting tour of the United States as seen by foreigners, and covered the 1972 Munich Olympics where he photographed a ski-masked Palestinian terrorist on the balcony of the building where Israeli athletes were being held hostage, hours before they were murdered at the airport.

The same year, he won a second Pulitzer Prize, along with Michel Laurent of the French Gamma photo agency, for gripping pictures of torture and executions in Bangladesh.

Mr. Laurent, who had once worked for The A.P. under Mr. Faas in Saigon, later became the last journalist killed in the Vietnam War, two days before the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. In 1976, Mr. Faas relocated to London as The A.P.’s senior photo editor for Europe, until he retired from the news agency in 2004. He was an editor of “Requiem,” a 1997 book about photographers killed on both sides of the Vietnam War, and was an author of “Lost Over Laos,” a 2003 book about four photographers shot down in Laos in 1971 and the search for the crash site 27 years later. http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/a-parting-glance-horst-faas/

Vanishing treasures of Asia

Asia's architectural treasures, from a Buddhist monastery in Afghanistan to an ancient city in China, are in danger of vanishing under a tide of economic expansion, war and tourism, experts said Thursday. The Global Heritage Fund named 10 sites facing "irreparable loss and destruction."

"These 10 sites represent merely a fragment of the endangered treasures across Asia and the rest of the developing world," Jeff Morgan, executive director of the fund, said, presenting the report, "Asia's Heritage in Peril: Saving Our Vanishing Heritage."

The architectural gems from Asia's ancient and sophisticated cultures are struggling in the face of economic expansion, sudden floods of tourists, poor technical resources, and areas blighted by looting and conflict -- in other words, the pressures of rapidly modernizing Asia.

"We're looking at these millennial civilizations leapfrogging into the 21st century at a kind of pace that is unheard of, unprecedented," said Vishakha N. Desai, president of the Asia Society, which hosted a conference based on the report.

Kuanghan Li, head of Global Heritage Fund's China program, underlined the urgency in a presentation on work to preserve Pingyao, one of China's last surviving walled cities. The stunning fortifications are impressively maintained and floodlit. But "up to 20 years ago, there were hundreds of similar walled cities left in China," she said. "They have been demolished."

Experts said that global architectural preservation efforts are poorly coordinated and targeted, with the UN cultural body UNESCO focusing almost entirely on sites in already wealthy European countries, rather than in places like Latin America or Asia. More than 80 percent of UNESCO World Heritage sites are located in the 10 richest states, the Global Heritage Fund said.

Elsewhere, "heritage is being dramatically undervalued," Morgan said, warning that the endangered sites were doomed without quick help. "We're going to lose them on our watch in the next 10 years." Shirley Young, head of the US-China Cultural Institute, said the importance of such work goes beyond being "just about beautiful buildings, beautiful sites." "I think we'd agree," she said, "that a world without history is a world without soul." Still, experts highlighted stories of inspiring success stories.

John Sanday, a specialist who has spent years trying to bring Angkor and other Cambodian sites back from the brink of collapse, showed dramatic before-and-after photographs of majestic temples that he first encountered two decades ago. "The trees had literally just taken over and strangling the building, pulling it apart," he said, pointing to ruins that had been made structurally sound once again -- although now under threat from tourism.

"We really hope with a concerted effort we can save these places," Morgan said. The top 10 endangered sites in Asia, according to the Global Heritage Fund, are:

1. Ayutthaya in Thailand, a former Siamese capital known as the "Venice of the East."

2. Fort Santiago in the Philippines.

3. Kashgar, one of the last preserved Silk Road cities in China.

4. Mahasthangarh, one of South Asia's earliest archeological sites in Bangladesh.

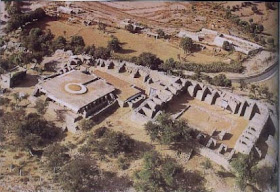

5. Mes Aynak, an Afghan Buddhist monastery complex on the Silk Road.

6. Myauk-U, capital of the first Arakenese kingdom in Myanmar.

7. Plain of Jars, a mysterious megalithic site in Laos.

8. Preah Vihear, a Khmer architectural masterpiece in Cambodia

9. Rakhigari, one of the biggest, ancient Indus sites in India.

10. Taxila, an ancient economic crossroads in Pakistan.

"These 10 sites represent merely a fragment of the endangered treasures across Asia and the rest of the developing world," Jeff Morgan, executive director of the fund, said, presenting the report, "Asia's Heritage in Peril: Saving Our Vanishing Heritage."

The architectural gems from Asia's ancient and sophisticated cultures are struggling in the face of economic expansion, sudden floods of tourists, poor technical resources, and areas blighted by looting and conflict -- in other words, the pressures of rapidly modernizing Asia.

"We're looking at these millennial civilizations leapfrogging into the 21st century at a kind of pace that is unheard of, unprecedented," said Vishakha N. Desai, president of the Asia Society, which hosted a conference based on the report.

Kuanghan Li, head of Global Heritage Fund's China program, underlined the urgency in a presentation on work to preserve Pingyao, one of China's last surviving walled cities. The stunning fortifications are impressively maintained and floodlit. But "up to 20 years ago, there were hundreds of similar walled cities left in China," she said. "They have been demolished."

Experts said that global architectural preservation efforts are poorly coordinated and targeted, with the UN cultural body UNESCO focusing almost entirely on sites in already wealthy European countries, rather than in places like Latin America or Asia. More than 80 percent of UNESCO World Heritage sites are located in the 10 richest states, the Global Heritage Fund said.

Elsewhere, "heritage is being dramatically undervalued," Morgan said, warning that the endangered sites were doomed without quick help. "We're going to lose them on our watch in the next 10 years." Shirley Young, head of the US-China Cultural Institute, said the importance of such work goes beyond being "just about beautiful buildings, beautiful sites." "I think we'd agree," she said, "that a world without history is a world without soul." Still, experts highlighted stories of inspiring success stories.

John Sanday, a specialist who has spent years trying to bring Angkor and other Cambodian sites back from the brink of collapse, showed dramatic before-and-after photographs of majestic temples that he first encountered two decades ago. "The trees had literally just taken over and strangling the building, pulling it apart," he said, pointing to ruins that had been made structurally sound once again -- although now under threat from tourism.

"We really hope with a concerted effort we can save these places," Morgan said. The top 10 endangered sites in Asia, according to the Global Heritage Fund, are:

1. Ayutthaya in Thailand, a former Siamese capital known as the "Venice of the East."

2. Fort Santiago in the Philippines.

3. Kashgar, one of the last preserved Silk Road cities in China.

4. Mahasthangarh, one of South Asia's earliest archeological sites in Bangladesh.

5. Mes Aynak, an Afghan Buddhist monastery complex on the Silk Road.

6. Myauk-U, capital of the first Arakenese kingdom in Myanmar.

7. Plain of Jars, a mysterious megalithic site in Laos.

8. Preah Vihear, a Khmer architectural masterpiece in Cambodia

9. Rakhigari, one of the biggest, ancient Indus sites in India.

10. Taxila, an ancient economic crossroads in Pakistan.

Lessons from Cyrus the Great: A more humane perspective

9 Timeless Leadership Lessons from Cyrus the Great

http://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholiday/2012/04/19/9-timeless-leadership-lessons-from-cyrus-the-great/

The greatest book on business and leadership was written in the 4th century BC by a Greek about a Persian King. Yeah, that’s right. Behold: Cyrus the Great, the man that historians call “the most amiable of conquerors,” and the first king to found “his empire on generosity” instead of violence and tyranny. Consider Cyrus the antithesis to Machiavelli’s ideal Prince. The author, himself the opposite of Machiavelli, was Xenophon, a student of Socrates.

The book is a veritable classic in the art of leadership, execution, and responsibility. Adapted from Larry Hendrick’s excellent translation, here are nine lessons in leadership from Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great (NB: And the historical traditions of the Hittites) :

1. Be Self-Reliant “Never be slow in replenishing your supplies. You’ll always bee on better terms with your allies if you can secure your own provisions…Give them all they need and your troops will follow you to the end of the earth.”

2. Be Generous “Success always calls for greater generosity–though most people, lost in the darkness of their own egos, treat it as an occasion for greater greed. Collecting boot [is] not an end itself, but only a means for building [an] empire. Riches would be of little use to us now–except as a means of winning new friends.”

3. Be Brief “Brevity is the soul of command. Too much talking suggests desperation on the part of the leader. Speak shortly, decisively and to the point–and couch your desires in such natural logic that no one can raise objections. Then move on.”

4. Be a Force for Good “Whenever you can, act as a liberator. Freedom, dignity, wealth–these three together constitute the greatest happiness of humanity. If you bequeath all three to your people, their love for you will never die. [NB: This explains the rise, fall and longevity of the political instutions, nations and civilizations that we know of] ”

5. Be in Control [After punishing some renegade commanders] “Here again, I would demonstrate the truth that, in my army, discipline always brings rewards.”

6. Be Fun “When I became rich, I realized that no kindness between man and man comes more naturally than sharing food and drink, especially food and drink of the ambrosial excellence that I could now provide. Accordingly, I arranged that my table be spread everyday for many invitees, all of whom would dine on the same excellent food as myself. After my guests and I were finished, I would send out any extra food to my absent friends, in token of my esteem.”

7. Be Loyal [When asked how he planned to dress for a celebration] “If I can only do well by my friends, I’ll look glorious enough in whatever clothes I wear.”

8. Be an Example “In my experience, men who respond to good fortune with modesty and kindness are harder to find than those who face adversity with courage.”

9. Be Courteous and Kind “There is a deep–and usually frustrated–desire in the heart of everyone to act with benevolence rather than selfishness, and one fine instance of generosity can inspire dozens more. Thus I established a stately court where all my friends showed respect to each other and cultivated courtesy until it bloomed into perfect harmony.”

There’s a reason Cyrus found students and admirers in his own time as well as the ages that followed. From Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin to Julius Caesar and Alexander (and yes, even Machiavelli) great men have read his inspiring example and put it to use in the pursuit of their own endeavors. That isn’t bad company.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholiday/2012/04/19/9-timeless-leadership-lessons-from-cyrus-the-great/

The greatest book on business and leadership was written in the 4th century BC by a Greek about a Persian King. Yeah, that’s right. Behold: Cyrus the Great, the man that historians call “the most amiable of conquerors,” and the first king to found “his empire on generosity” instead of violence and tyranny. Consider Cyrus the antithesis to Machiavelli’s ideal Prince. The author, himself the opposite of Machiavelli, was Xenophon, a student of Socrates.

The book is a veritable classic in the art of leadership, execution, and responsibility. Adapted from Larry Hendrick’s excellent translation, here are nine lessons in leadership from Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great (NB: And the historical traditions of the Hittites) :

1. Be Self-Reliant “Never be slow in replenishing your supplies. You’ll always bee on better terms with your allies if you can secure your own provisions…Give them all they need and your troops will follow you to the end of the earth.”

2. Be Generous “Success always calls for greater generosity–though most people, lost in the darkness of their own egos, treat it as an occasion for greater greed. Collecting boot [is] not an end itself, but only a means for building [an] empire. Riches would be of little use to us now–except as a means of winning new friends.”

3. Be Brief “Brevity is the soul of command. Too much talking suggests desperation on the part of the leader. Speak shortly, decisively and to the point–and couch your desires in such natural logic that no one can raise objections. Then move on.”

4. Be a Force for Good “Whenever you can, act as a liberator. Freedom, dignity, wealth–these three together constitute the greatest happiness of humanity. If you bequeath all three to your people, their love for you will never die. [NB: This explains the rise, fall and longevity of the political instutions, nations and civilizations that we know of] ”

5. Be in Control [After punishing some renegade commanders] “Here again, I would demonstrate the truth that, in my army, discipline always brings rewards.”

6. Be Fun “When I became rich, I realized that no kindness between man and man comes more naturally than sharing food and drink, especially food and drink of the ambrosial excellence that I could now provide. Accordingly, I arranged that my table be spread everyday for many invitees, all of whom would dine on the same excellent food as myself. After my guests and I were finished, I would send out any extra food to my absent friends, in token of my esteem.”

7. Be Loyal [When asked how he planned to dress for a celebration] “If I can only do well by my friends, I’ll look glorious enough in whatever clothes I wear.”

8. Be an Example “In my experience, men who respond to good fortune with modesty and kindness are harder to find than those who face adversity with courage.”

9. Be Courteous and Kind “There is a deep–and usually frustrated–desire in the heart of everyone to act with benevolence rather than selfishness, and one fine instance of generosity can inspire dozens more. Thus I established a stately court where all my friends showed respect to each other and cultivated courtesy until it bloomed into perfect harmony.”

There’s a reason Cyrus found students and admirers in his own time as well as the ages that followed. From Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin to Julius Caesar and Alexander (and yes, even Machiavelli) great men have read his inspiring example and put it to use in the pursuit of their own endeavors. That isn’t bad company.

Genghis Khan: Caution - Controversial article.

[Blogger's note: This article may be CONTROVERSIAL].

Take from Forbes magazine: http://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholiday/2012/05/07/9-lessons-on-leadership-from-genghis-khan-yes-genghis-khan/?partner=forbespicks

On one end of the leadership spectrum, there is Machiavelli–conniving, ambitious and ruthless. On the other there is Cyrus the Great–humble, generous and loyal. Along this spectrum of great leaders and motivators, used so often in business books, speeches and anecdotes, there is one unmentionable: Genghis Khan. A man so evil, unwashed and bloodthirsty that he is impossible to learn from. Or so the efforts to suppress his influence would have us believe. (The USSR, for instance, cleared out Khan’s homeland in Mongolia and forbade any mention of him.)

But I’m here to tell you that we can learn more about leadership and getting things done from Genghis Khan than just about any other historical figure. Because almost everything you know about him is wrong

For starters: he abolished torture, embraced religious freedom, united disparate tribes, hated aristocratic privilege, ran his kingdoms meritocratically, loved learning and advanced the rights of women in Mongol society. [Note: I'm not so sure about the running of his kingdoms method though]

He was also the greatest conqueror and general who ever lived, ruling a self-made kingdom of nearly 12-million square miles which lasted in parts for nearly seven centuries. (When United States forces captured Baghdad they were the first successful invaders to take the city since Khan.)

Yes, he was violent and war-like, but never for its own sake. The Mongols found no honor in fighting–only winning. Victory was their aim and they did whatever it took to get it. Then they focused on building peace with equal intensity. [May have explained the short-lived Yuan Dynasty in China and elsewhere]. So while other conquerors died violent, early deaths, Khan died an old man surrounded by his loving family.

1. Have An End in Mind “For the Mongol warrior, there was no such thing as individual honor in battle if the battle was lost. As Genghis Khan reportedly said, there is no good in anything until it is finished.”

2. Lead from the Front “When it was wet, we bore the wet together, when it was cold, we bore the cold together.”

3. Serve a Greater Good Than Yourself “[A leader] can never be happy until his people are happy.”

4. Have a Vision “Without the vision of a goal, a man cannot manage his own life, much less the lives of others…The ancients had a saying: ‘Unity of purpose is a fortune in affliction.’”

5. Be Self-Reliant “No friend is better than your own wise heart! Although there are many things you can rely on, no one is more reliable than yourself. Although many people can be your helper, no one should be closer to you than your own consciousness (and conscience). Although there are many things you should cherish, no one is more valuable than your own life.”

6. Be Humble “The mastery of pride, which was something more difficult, he explained, to subdue than a wild lion. He warned them that, ‘If you can’t swallow your pride, you can’t lead.’”

7. Be Moderate “I hate luxury. I exercise moderation…It will be easy to forget your vision and purpose one you have fine clothes, fast horses and beautiful women. [In which case], you will be no better than a slave, and you will surely lose everything.”

8. Understand Your People “People conquered on different sides of the lake should be ruled on different sides of the lake.”

9. Change the World, But Change it Gradually “The vision should never stray far from the teaching of the elders. The old tunic fits better and it always more comfortable; it survives the hardships of the bush while the new or untried tunic is quickly torn.”

As Weatherford writes, these tenets of leadership did not come to Khan as part of some princely education. He was born poor and illiterate in a world of conflict and strife. He taught himself to be a Khan: “At no single, crucial moment in his life did he suddenly acquire his genius at warfare, his ability to inspire the loyalty of his followers, or his unprecedented skill for organizing on a global scale. These derived not from epiphanic enlightenment or formal schooling but from a persistent cycle of pragmatic learning, experimental adaptation and constant revision driven by his uniquely disciplined mind and focused will.” We can do the same. And we can do it by starting with the example of someone who at first might make us a little uncomfortable. Genghis Khan’s reputation precedes him (a brutal pillager who shows no mercy to men, women or children), but that was deliberate. Khan allowed rumors of his atrocities to spread to encourage surrender and cooperate from enemies who might otherwise resist. Putting that aside, we can learn from the Great Khan how to be loyal, how to understand our people, how to induce change and how to have a vision.

Take from Forbes magazine: http://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholiday/2012/05/07/9-lessons-on-leadership-from-genghis-khan-yes-genghis-khan/?partner=forbespicks